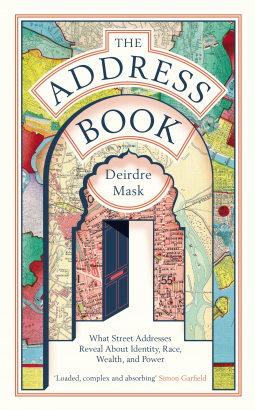

The Address Book

What Street Addresses Reveal about Identity, Race, Wealth and Power

by Deirdre Mask

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date 2 Apr 2020 | Archive Date 16 Mar 2020

Serpent's Tail / Profile Books | Profile Books

Talking about this book? Use #TheAddressBook #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

'Deirdre Mask’s book was just up my Strasse, alley, avenue and boulevard. A classic history of nomenclature - loaded, complex and absorbing.' - Simon Garfield

Starting with a simple question, 'what do street addresses do?', Deirdre Mask travels the world and back in time to work out how we describe where we live and what that says about us. From the chronological numbers of Tokyo to the naming of Bobby Sands Street in Iran, she explores how our address - or lack of one - expresses our politics, culture and technology. It affects our health and wealth, and it can even affect the working of our brains.

From Ancient Rome to Kolkata today, from cholera epidemics to tax hungry monarchs, Mask discovers the different ways street names are created, celebrated, and in some cases, banned. Filled with fascinating people and histories, this incisive, entertaining book shows how addresses are about identity, class and race. But most of all they are about power: the power to name, to hide, to decide who counts, who doesn't, and why.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Other Format |

| ISBN | 9781781259009 |

| PRICE | £16.99 (GBP) |

| PAGES | 320 |

Links

Featured Reviews

Yes, as in a whole book about addresses, part of that non-fiction genre which answers questions you didn't know you had about something which, at least if you live in the urban West, you've probably taken for granted as beneath the threshold of notice. But being from Profile/Serpent's Tail, not a publisher known for Christmas cash-ins (and indeed, it's not out until April), it takes a far more political angle than many such. We open in rural West Virginia, where most people don't have addresses and plenty would like to keep it that way, retaining a deep backwoods suspicion of the government in all its forms, even if the current set-up means people dying because paramedics can't follow idiosyncratic directions down confusing lanes. Amusingly, some chapters later in Vienna, one of the birthplaces of house numbers (like lightbulbs, they seemed to spring up all over around the same time), an expert on the subject tells the author they're right. Yes, there are house number experts, or one, at least – Anton Tantner, whose book House Numbers makes Mask's theme seem shamelessly broad by comparison. "House numbers, he tells his readers, were not invented to help you navigate the city or receive your mail, though they perform these two tasks admirably. Instead they were designed to find you, tax you, imprison you, protect you. Rather than helping you find your way, house numbers help the government find you." That's a few chapters on, though. First we jump from the American countryside to Tottenham, and a street I myself boggled at when I first passed it back in my North London days, where Mask briefly considered buying a house which had a lot in its favour; still, you can see why an African American writer might have opted not to live on Black Boy Lane.

Elsewhere, Mask visits the slums of Kolkata, where a new project is intending to give even the most makeshift dwellings addresses – albeit, she notes, on a different system to the city proper; imperfect improvements to a system broken on so many levels are a running theme in the book. In the meantime, it's dispiriting if hardly surprising that a home-grown, democratically elected communist government should have been just as ready to dismiss the slum-dwellers as the Raj ever was, concerned that giving them addresses would mean admitting they were there in the first place. Not that the city will be unique in having parallel systems, which turn out to be surprisingly common, albeit along various different axes: Czech houses have a number for government and another for directional use; in Florence, residential and business purposes have different numbers. And plenty of other ways have been found to make a mess of the whole business, not least when money gets involved. In NYC, addresses can be changed for $11,000 – peanuts in property developer terms. But even one of the city's most famous addresses, Times Square, turns out to have been a vanity renaming to match London's 'Arsenal' station (GILLESPIE ROAD WILL RISE AGAIN!). Nor is the issue unique to Manhattan; in Chicago, a woman named Nancy Clay died because firefighters hadn't realised that the building One Illinois Place wasn't actually situated on Illinois Place. Something horribly Grenfell about that death by property prices, which makes one take a real glee in one London project Mask finds, a solution to the problem whereby homeless people almost have as many problems following from not having an address as they do from not having a home. Now, the proposal runs, they can be given dummy addresses of unoccupied properties, which will forward to post offices or the like. And what's one of the biggest batches of unoccupied properties? The ones the wealthy have bought purely as investments and then left empty. Sure, it would be better to actually let the cold and hungry live in them, but in the meantime, nicking their coveted postcodes would be a wonderful start.

To the British reader, some stories may be familiar, such as that of postal reformer Rowland Hill. It's poignant to be reminded, having seen how well the idea of state-funded broadband went down, that the penny post was also "a measure many thought would bankrupt the nation", and which instead proved a huge money-spinner. But as with John Snow and his ghost map, Mask uses old stories to make newer points; in Snow's case, as a contrast with this decade's cholera outbreak in Haiti where, unlike in Snow's Soho, there were determined efforts at obfuscating the UN's responsibility. So a story usually produced to show how knowledge saves lives is flipped - and, as she points out, while Snow may have ended one local epidemic, the wholesale eradication of cholera as a feature of London life came with the great sewer-building works...which were largely about getting rid of 'miasma'. A less grave example: most of my smutty-minded compatriots will know about Gropecunt Lane, but here its appearance serves to set up a hilarious though apparently sincere passage of charming American innocence over the campaign to rename a street in the West Midlands town of Rowley Regis: "I thought it sounded elegant – the light trill of the word Bell paired with the serious and solid End."

I suppose the story of William Penn, Philadelphia and the birth of the US grid system may well be as familiar to Americans as Hill, Snow and Bell End are to us, but it was new to me. And I'm fairly sure no Briton could have written with such equanimity about the various streets around the world named for Bobby Sands – although, perhaps helped by her husband coming from Cookstown, Mask addresses the Troubles* with considerably more nuance than most American writers manage. Elsewhere she offers an intriguing investigation into whether linguistics affects addressing conventions, with reference to Japanese and Korean, albeit one which ends on a wonderfully bathetic note, and takes us to South Africa's Constitutional Court, where the judges don't split along the left-right lines of the US supreme court, or even racial ones - except when it comes to renaming streets. An area in which Mandela erred on the side of caution ("a tactic to make the revolution seem less revolutionary"), but his successor Mbeki veered the other way. Some of these were names including racial slurs, or commemorating Afrikaaner heroes, where one can entirely see his point - but then you get to Mangosuthu Highway, named for an Inkatha Freedom Party leader, where switching that to ANC activist Griffiths Mxenge is nothing nobler than party favouritism. These complex, imperfect situations recur over and over, right through to the conclusion, where Mask talks about the way projects such as what3words usefully offer addresses for the previously unaddressable, while also noting that as the product of for-profit tech firms, the potential implications are troubling. Along the way we look at whether Romans had addresses, and if not how they managed, and encounter the concept of 'imageability', or more widely memorability, which explains why Boston and Florence are easier to navigate than Jersey City. It's a book of which I've been dropping snippets into conversations since I started reading it, and which I'd be buying at least one person for Christmas if only it weren't for that aforementioned release date issue. Ah well, maybe next year, if only we aren't all living amidst the rubble by then.

*I suppose that's yet another 20th century franchise due for an unwanted reboot soon.

Readers who liked this book also liked:

Rick Riordan; Mark Oshiro

Children's Fiction, LGBTQIA, Teens & YA

Keith Martin; Konstantinos Mersinas; Guido Schmitz; Jassim Happa

Business, Leadership, Finance, Computers & Technology, Reference

Vincent B. "Chip" LoCoco

Historical Fiction, Horror, Mystery & Thrillers