The MANIAC

by Benjamín Labatut

This title was previously available on NetGalley and is now archived.

Send NetGalley books directly to your Kindle or Kindle app

1

To read on a Kindle or Kindle app, please add kindle@netgalley.com as an approved email address to receive files in your Amazon account. Click here for step-by-step instructions.

2

Also find your Kindle email address within your Amazon account, and enter it here.

Pub Date 7 Sep 2023 | Archive Date 25 Oct 2023

Talking about this book? Use #TheMANIAC #NetGalley. More hashtag tips!

Description

From the author of When We Cease to Understand the World: a dazzling, kaleidoscopic book about the destructive chaos lurking in the history of computing and AI

Johnny von Neumann was an enigma. As a young man, he stunned those around him with his monomaniacal pursuit of the unshakeable foundations of mathematics. But when his faith in this all-encompassing system crumbled, he began to put his prodigious intellect to use for those in power. As he designed unfathomable computer systems and aided the development of the atomic bomb, his work pushed increasingly into areas that were beyond human comprehension and control – and that threatened human destruction.

In The MANIAC, Benjamín Labatut braids fact with fiction in a scintillating journey to the very fringes of rational thought, right to the point where it tips over into chaos. Stretching back to early twentieth-century conflict over contradictions in physics and up to advances in artificial intelligence that outpace the human, this is a mind-bending story of the mad dreams of reason.

Available Editions

| EDITION | Hardcover |

| ISBN | 9781782279815 |

| PRICE | £20.00 (GBP) |

| PAGES | 368 |

Available on NetGalley

Featured Reviews

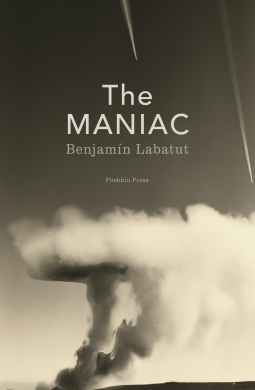

As a descendant of a nuclear test veteran, the second I saw the cover of this one, I knew I had to read it.

This did feel to me that it was written like it was fact rather than fiction, and I know that there are blurred lines with what is fact and fiction here, but I wasn't sure about this.

The subject matters are eerie, and dark, but important.

Thought provoking, if not a little stressful!

Labatut has written a book which is utterly compulsive... and wholly terrifying. His theme is the development of scientific learning, both the incomparable glory of human inventiveness and pure intellectual brilliance, and the horrifying spectre of what happens when that search for knowledge has no moral or humanistic bounds or limitations.

The ultimate journey is towards AI but there's already a gap between where the book ends and our world, ending as it does with self-learning Go/chess computers. The itinerary takes some time to get there though with much time spent with Janos/John von Neumann, mathematician, physicist and computer scientist. His contributions to twentieth-century knowledge are jaw-dropping: from pure mathematics and quantum mechanics to the development of the atom and hydrogen bombs, from game theory and the mathematical basis of rational decision-making as harnessed during the Cold War to the development of non-human/digital intelligence.

But what is chilling is von Neumann's eradication of all moral limits: he stands against other international nuclear physicists who sign a joint letter to Eisenhower saying that the atom bomb should never be used; he is the one who works out precisely how high above Hiroshima and Nagasaki the bombs should be detonated to cause maximum destruction and death; and he came up with the acronym MAD (Mutual Assured Destruction) during the Cold War with advice to launch a pre-emptive strike on the USSR in line with his game theory model.

The story is told via narratives from von Neumann's colleagues, friends, wives, and intellectual enemies. I wish there had been an afterword detailing what is fact and what fiction: Labatut notes his sources but otherwise doesn't comment on this point.

For me, though, the book changes once von Neumann dies and the focus turns to the development of AI gaming computers - I struggled to maintain much interest in the detailed game-by-game record of Go and chess against international masters. Up until this point, about 70-75% of the way through, this would have been a 5-star book for me but, somehow, despite the importance of the topic, the final quarter fell away.

Still, for most of the time this is a veritable page-turner, albeit one which I found stressful to read. It feels more wholly 'factual' than When We Cease to Understand the World and reveals those scary scenarios without comment.

Graham F, Reviewer

Graham F, Reviewer

Benjamin’s Labatut’s “When We Cease to Understand the World”, as translated by Adrian Nathan West was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize (where it was only beaten by a stable mate from Pushkin Press). A brilliant and intellectually stimulating book it was a clever blend of fact and non-fiction based novel – starting with an almost entirely non-fiction section, then two short stories and a novella (with the fictional content increasing each time) and with a short meta-fictional conclusion.

Its subject was described in the book itself as “what happens when we reach the edges of science; when we come face to face with what we cannot understand. It is about what occurs to the human mind when it pushes past the outer limits of thought, and what lies beyond those limits.” – proceeding via the chemical production of both fertilizers and death camp gases, to the scientist Karl Schwarzcschild (a general relativist), the abstract mathematicians Mochizuki and Alexander Grothendieck to the meat of the book – the two (Schrodinger and Heisenberg/Bohr) rival interpretations of Quantum mechanics and those scientists links to the US and German atomic war programmes.

Now this novel is in many ways a sequel to that book – interestingly though not-translated with the author writing (I believe) his first English language novel.

It is though I would say a less innovative blend of fiction/non-fiction: with two almost (if not) entirely non-fictional sections bookending what is for the large part a relatively conventional fictional retelling of fact – using the not uncommon device of having a range of different first party characters effectively assembling for the reader by their reminiscences, a biography of the central character – the brilliantly and almost unbelievably widely prolific, but seemingly morally vacuous, Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, scientist, engineer, inventor of Game Theory, the Mutually-Assured-Destruction policy, vital and (in contrast to many of his fellow scientists) enthusiastic participant in the Manhattan Project – János/John/Jonnie von Neumann.

The first section “PAUL: or The Discovery of the Irrational” is the most obvious follow on from the earlier novel. A short and very factual section (around 10% of the book), it tells of the life (and death by suicide) of the Austrian Physicist Paul Ehrenfest. A contemporary of Bohr, Dirac, Pauli and Einstein and seen by all as a peer for his ability to synthesise, teach and his insistence on getting to “the leaping point, the heart of the matter” and seeking for a deep understanding of Physics – acting as something of a Conscience for the subject. Ehrenfest though became increasingly depressed by a combination of the rising Nazification of Germany and the implications for his institutionalised and handicapped son (who he murdered immediately before his suicide) and by the (for him) descent of Physics into illogical results justified by tricks, “brute-force artillery and mathematical formulae” – thus rendering him unable to bring his usual insights to bear.

The middle section “JOHN or The Mad Dreams of Reason” forms not just the bulk (around 65%) but the heart of the novel from which it draws its real impact – a section that is in many ways chilling to read. As per the above it tells the life of John von Neumann through a series of first party accounts by a those who encounter him both in Hungary and later America – from birth family, to early tutors, to wife and daughter, friends and particularly colleagues across the disciplines of Physics, Mathematical Economics, IT and Biology, including: Richard Fenyman (who recounts the story of Von Neumann’s involvement with the Manhattan Project), Eugene Wigner (another Hungarian Physicist) , Oskar Morgenstern (who developed Game Theory with von Neumann), Julian Bigelow (who worked with von Neumann on his first computer) and the eccentric Artificial Life researcher Nils Aall Barricelli. The accounts are mainly conventional in nature (effectively like the edited scripts of talking head documentaries) and factual in content (with perhaps only Barricelli’s account really having an imaginative leap). The section has a huge breadth of linked ideas ,and while the breadth and links are perhaps owed much more to the subject than the author, nevertheless this is an impressive piece of synopsis. Von Neumann is seen by those around him as almost unhuman in his incredible ability not just to range across subjects and disciplines but to practically invent and develop them from nothing; but he also comes across as unfeeling and amoral – for example not signing the letter from his fellow Manhattan Project scientists asking for the bomb not to be dropped but instead working out the height at which it should detonate to cause maximum deaths, later developing much of modern computing (and the titular computer) with the aim of developing a post War Hydrogen Bomb.

The final section “LEE or The Delusions of Artificial Intelligence” is in my view overly long (some 25%) and a missed opportunity. It tells the development of computers to take on and beat the world’s best players in Chess, and the main focus, Go – including the pivotal defeat of Sodol Lee by the Alpha Go machine. The content, again as far as I can see, is not just entirely factual but also I think well rehearsed . The style reminded me as a I read of a series of WIRED articles.

And while I understand that the idea of Games is one that holds the novel together and that the author makes explicit links between von Neumann and Chess/Go (references to Go tournaments at the Manhattan Project, the MANIAC computer being the first that could defeat a human opponent at chess (admittedly an unskilled human and a rudimentary version of the game) – I felt that there were opportunities missed: for example the second section ends with a discussion of the technological singularity and particularly for a late 2022 publication the lack of any reference to large language model chatbots is glaring; further I was surprised not to see a reference to Quantum computing which would have been an opportunity not just perhaps to add a more fictional / dream like aspect to this section (rather than a complete reversal to straight, if engagingly written, non-fiction) but also a chance to link to the ideas of both the first part of this novel and to the core of its predecessor.

So a very good book but which I feel missed the opportunity to be excellent and feels a slight regression from “When We Cease to Understand the World”. (although so are most books!)

Emma S, Bookseller

Emma S, Bookseller

When We Cease to Understand the World instantly became one of my all time favourite books in 2020 and I have been impatiently awaiting this next installment ever since. The MANIAC very lightly fictionalises advances in 20th century physics from the development of the nuclear bomb to the advent of AI, focusing largely on the life of Hungarian polymath Jon Van Neumann. Polyphonic, terrifying and utterly beautiful, the story turns out to be a real page-turner.

The MANIAC by Benjamín Labatut is a remarkable piece of literature that weaves together elements of reality and imagination, creating a narrative that compels us to contemplate the profound existential inquiries that define our human experience. With its beauty and relentless momentum, the novel provokes us to confront the most fundamental questions that shape our existence.

Chiara M, Book Trade Professional

Chiara M, Book Trade Professional

With The Maniac Benjamin Labatut confirms himself as one of the most original and relevant writers today. He has a very personal and new way to blend fiction and non-fiction, which is his thing. But there's something more in his writing, something brilliant and visceral, with remembrances of the GOAT, Roberto Bolano. Excellent book, indeed.